De-stress over anthracnose

Anthracnose has become the most hotly discussed disease in turf management over recent seasons, according to the latest list of Top 10 Turf Topics raised with STRI.

While microdochium patch can undoubtedly have serious impacts with a severe autumn outbreak, most greenkeepers have a good understanding of the risks, along with an integrated turf management (ITM) plan in place and ready to enact.

Anthracnose, however, appears to be an increasing issue. The pathogen itself is relatively weak and, even when present throughout the season, healthy plants are reasonably able to withstand infections, writes Syngenta Technical Manager, Sean Loakes.

The problems arise when plants are weakened by stress or injury and less able to resist disease development. Often plants can cope with one stress, but when multiple factors accumulate, the impacts of anthracnose can be both quick and catastrophic. What makes it harder to plan for is the effects of stress early in the season, may only become apparent with disease outbreaks later in the summer.

That has been exacerbated in recent years, when some of the stress factors imposed on turf have become increasingly more severe and prolonged. Those stresses can be both natural – weather related heat, light and drought or nutritional shortfall – or induced by necessary turf management practices.

Reducing the intensity of mowing can be the first step in cutting stress on the plant. That can be both the height of cut and the frequency of mowing. With a green cut set at 3.0 mm, even going to 3.3 mm gives the plant 10% more leaf area for photosynthetic activity and strength.

Trials have shown a tighter sward from a Primo Maxx II programme can have the same, or better, green speed cut at 3.3 mm, compared to an untreated at 3.00 mm.

Furthermore, the slightly raised cut was showed significantly smoother ball roll, which in player surveys was more attractive to golfers than speed alone.

Research in the US has shown raising the height of cut, from 2.8 mm to 3.2 mm, reduced the average incidence of anthracnose infection over the late summer by 18%. Cutting at a height of 3.6 mm in the trials reduced disease by 36%, compared to the lower cut. Recommendations from that trial indicated the best strategy was to double cut and roll at the higher cut of 3.6 mm, rather than reduce the height of cut.

Recent studies of mowing height have also revealed that heavier mowing units, often associated with battery powered equipment or incorporated groomer / brush technology and more blades, can result in actual cutting heights being lower than conventional units set to the same height on the bench. Using a prism gauge to check and adjust units to what is actually happening can avoid this problem, as well as checking the cleanness of cut that will also minimise stress.

Greens in a good growth regulation programme also perform more consistently all day, reducing the need for a labour intensive late-afternoon cut. It can also facilitate more use of a turf iron as an alternative to mowing in some instances, which further reduces stress on the turf while maintaining speed and smoothness.

Maintaining adequate nutrition is essential to avoid stressing plants. That is particularly important through prime growing conditions, which can help to build a buffer of carbohydrate strength in the plant that will help it counter stress through more difficult periods.

With the effect of sky-high energy prices impacting on fertiliser costs there may be an inclination to reduce inputs. However, all the studies have shown that turf under low nutrient management regimes is at far higher risk of anthracnose outbreaks. The actual amount required will be different for every situation, but trials have consistently shown 2 – 4 kg N/ha per week is a good base to minimise the risk of anthracnose.

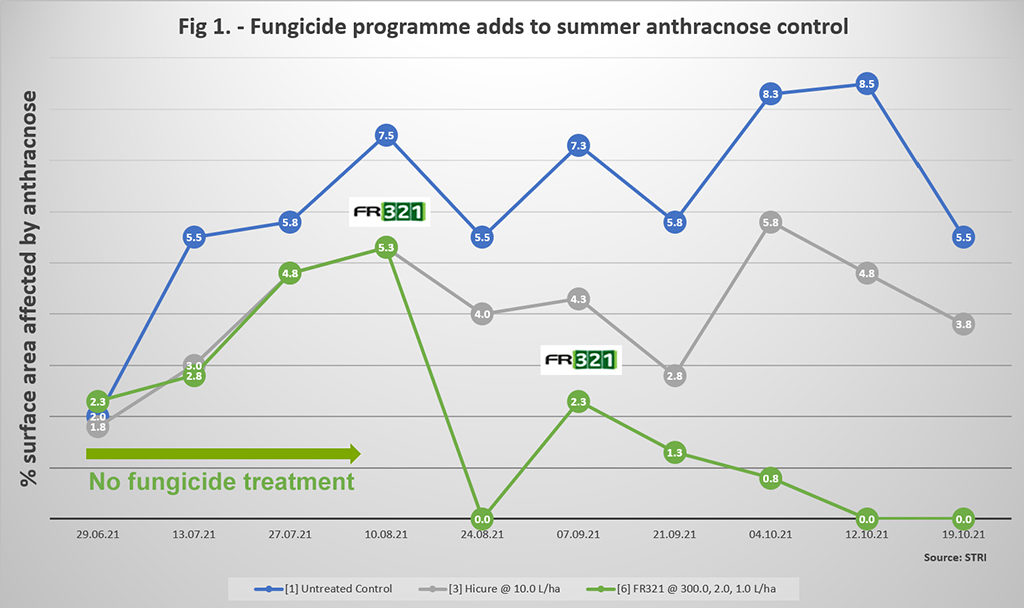

Alongside nutrition, STRI trials with the biostimulant, Hicure, have shown when used in a regular programme during the summer months plant health was improved, which in turn led to a reduction in anthracnose pressure of around 40% lower than in untreated areas.

As an ITM strategy, the trials also showed that a fungicide treatment was extremely effective at preventing anthracnose developing – giving up to 93% control compared to untreated. Where the fungicide programme was used and overlaid on top of a Hicure programme achieved the greatest levels of control and were most consistent and best over the course of the season.

Further STRI research in 2021 reported the FR321 fungicide one box solution – containing both Heritage and Medallion TL – kept anthracnose infection at 2% or less from the end of August and through September.

Top dressing had previously been considered a stress factor that could increase anthracnose risk. However new research indicates that, in itself, there is little or no increased risk. In fact reducing surface organic matter and improving firmness and smoothness proves to be beneficial. Good practice suggests light and frequent treatments – of 5 t/ha every fortnight – would be preferential, with any heavy dressing of 40 t/ha better applied in the spring, rather than the autumn.

One of the ‘additive’ stresses, that may not have been sufficiently considered in the past, is light. Turf that is managed on the edge for nutrition, cutting height and moisture, for example, that is performing exceptionally, could be tipped over into high anthracnose risk category by excess light.

Studies have shown that once light hits over 600 micromoles per second, turf plants can no longer cope with all the electrons produced by all the photosynthetic activity. As a result, the electrons, or free radicals, produced and not utilised by the plant actually become damaging to the cells. If plants are already under stress from, other factors, that may be too much.

One option could be to back off on some of the other stress inducing factors, such as height of cut, which in itself may have a detrimental impact on the playing conditions.

Alternatively, using the pigment Ryder, with a built in UV screen, could enable the plant to cope with the excess light and maintain the optimum surface quality.

In addition to the interacting induced stress factors, weather stress has also increased in recent seasons. Anthracnose is initially triggered by high temperatures and moisture when plant stress is greater. Periods of excessive heat are seemingly shifting upwards with the changing climate.

Prolonged hot, dry periods that have become the norm do increase the risk of plant stress. It can be further exacerbated where irrigation is more frequent to counter any drought, when the high humidity and leaf wetness during hot weather are the perfect conditions for anthracnose to develop.

That makes irrigation scheduling and wetting agent programmes an essential part of any season-long ITM programme to minimise the risk of anthracnose. Then, using turf specific weather forecasting tools, such as Syngenta’s WeatherPro, can help to make decisions on short-term adaptations to avoid stress, and that could avert an outbreak.