Climate warms up for pest activity

Warmer temperatures are undoubtedly becoming the norm. Changing weather patterns and the trend to greater extremes, are having significant impacts on everyday turf management decisions, and a key part of longer term planning.

One of the hot topics for consideration is the implication for leatherjackets and turf pests, writes Syngenta Technical Manager, Glenn Kirby (below).

Warmer winters could prove one of the key factors in increasing pest issues on affected courses. Experience in recent seasons has highlighted damaging pest infestations can be very localised, to just one or two courses in an area, or even one or two holes within a course.

But, as weather conditions and turf management practices become more conducive to pest activity, the extent of damage is creeping out, particularly with leatherjackets.

Like most soil borne insect pasts, including chafer grubs, the life cycle of leatherjackets typically incorporates a winter diapause, or state of suspended animation, when young larvae are no longer actively feeding.

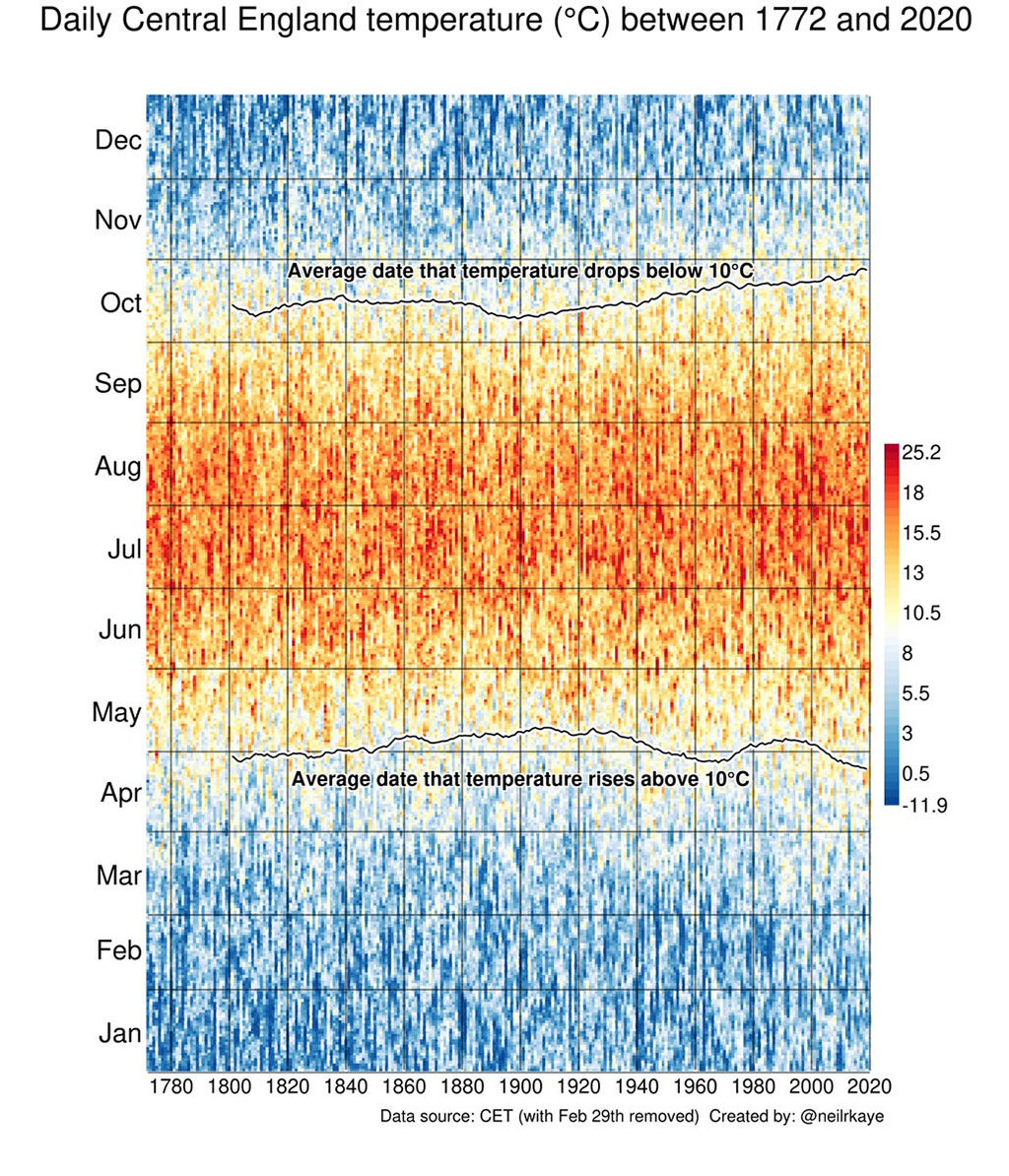

But with soil temperatures typically remaining warmer for longer in the autumn (Fig 1), along with heating up earlier in the spring, the diapause period may be shorter, and in some instances not actually occur at all. The result is greater potential for extended activity and feeding - with associated damage - along with faster growth that can make pests too large to control.

Fig 1. Long-term records show the average dates temperatures exceed 10°C are occurring earlier in the spring and later in the autumn, extending periods of pest activity.

We have also seen on golf courses that leatherjackets are actually quite mobile when surface conditions are cool and moist. Mild winters increase opportunities to emerge and relocate.

They do appear quite adept at spreading themselves evenly across any given area – to give themselves the best availability to food source and minimise the risk of predation.

Inspection of affected green will typically find leatherjackets safely residing in aeration holes, just surfacing at night to feed on turf around the entrance – and leading to little pock marks that infuriatingly affect smoothness and ball roll. But you will rarely find more than one leatherjacket in any hole, and they will be pretty evenly spaced.

That also has implications for control strategies, since even if good control is achieved on a treated green, other leatherjackets may simply move in to take their place in what are ideal living conditions for the pest. The longer weather conditions remain warm into the winter, the greater the potential for movement and reinfestation.

Pest Tracker

There is also evidence that pests are able to tailor emergence to seasonal conditions year-on-year, and longer term to climate change. Many pest predictions are based on soil temperatures and Growing Degree Day models. In the US, the Syngenta Weevil Track has become a key tool to tailor Aceleypryn application timing to pest activity.

The data from PestTracker over the past two seasons shows that whilst total population recorded have been incredibly similar, numbers seen each individual week can be significantly different.

That would appear to indicate, not unreasonably, that weather and soil conditions could be a factor in adult emergence – or at least their activity.

Whilst it does show the differences year on year, there is only marginal difference across the UK as to when the pests are been seen – and since GDD is extremely variable between locations, would tend to indicate that other forces, such as day length, rainfall or combination of factors are in play.

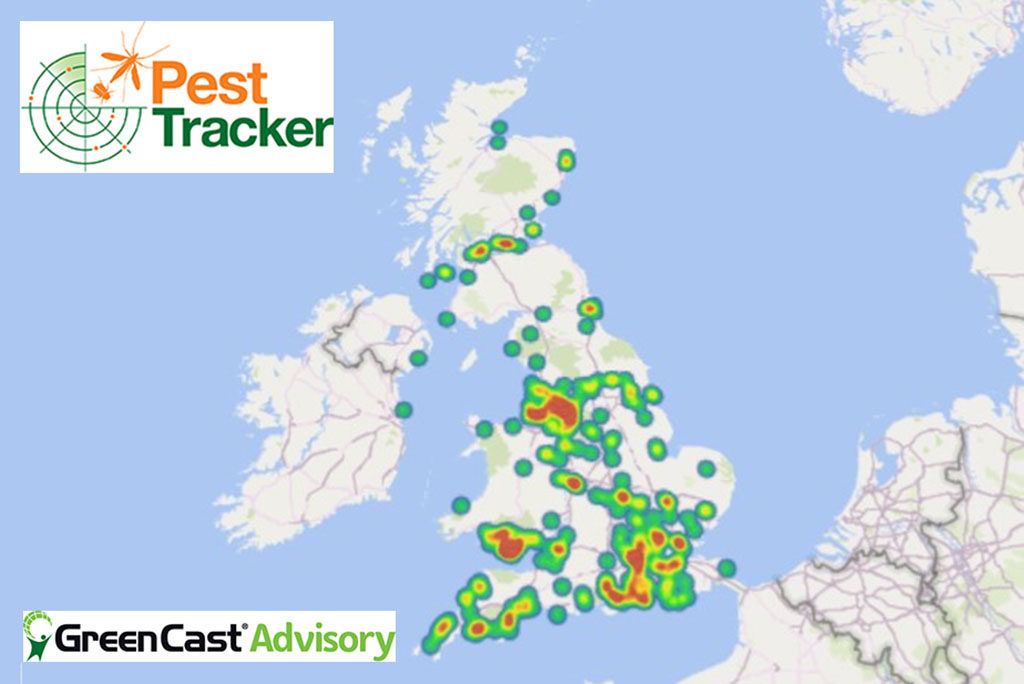

Fig 2. Heat maps of Pest Tracker reports for autumn crane fly activity in 2019 pinpoint areas of highest risk.

Pest Tracker results have already been extremely useful as picture of when and where pests are active (Fig 2.). With the capture of more results and data, particularly regular reporting from the same site including periods of no activity, and then when the first adults are seen, would be invaluable information to match to environmental conditions to develop of a soil pest emergence model for the UK.

Turf models

The problem for turf is that most of the modelling for pest species change is for agricultural pests, under typical farming systems and the natural environment.

For example, entomological assessment would suggest that warmer temperatures and prolonged dry periods, resulting in baked-hard, drier soils, would be more inhospitable to leatherjackets as an agricultural pest. With turf surfaces, however, using irrigation and aeration and a permanently available food source, it artificially creates near perfect conditions for crane fly egg laying and leatherjacket development.

Pest modelling specialists have identified that some pests that target specific growth stages of a plant may experience mismatches between its life cycle and the host, thus reducing damaging effects. However, for turf pests where the environment is ever present, there is little downside from changing patterns of emergence, for example.

In fact, issues could potentially be exacerbated if beneficial natural predators do not adapt to emerge at the same time as the pests.

Typically any imbalances will resolve over time, but there is the potential for greater short-term issues.

Some ecologists had suggested that if temperatures rise it could have a negative impact on all insect populations, including pests. However, further detailed studies have highlighted likely changes are dependent on whether existing conditions are deemed optimal for individual species.

Not unreasonably, the research concluded that, if an insect is at its optimal point, or above, and temperatures rise, it would have a negative effect; but if it is currently below optimal then any increase in temperature would be beneficial and the pest problem exacerbated.

Heating up

If we look at the case of leatherjackets, for example, Syngenta colleagues report the pests are a serious problem in turf throughout France, from north to south, where temperatures are typically several degrees hotter. They reported that leatherjacket issues where especially bad on greens over the past winter, attributed to the particularly warm conditions.

That would indicate that UK populations could quite comfortably cope with current climate change predictions, and could potentially become worse.

The positive point is that whilst crane flies are mobile and could potentially migrate as weather conditions change, their life cycle is predominantly to lay eggs soon after emergence, staying within the close locality.

That tends to be why some courses suffer repeated infestations year after year, whilst others even locally may suffer little damage. It also suggests limited risk of movement of other crane fly species, of which there are many hundreds, into the UK in the short term.

Longer term, the more understanding of the life-cycle and emergence patterns of leatherjackets and chafer grubs we can gain through Pest Tracker, the better we can utilise integrated control measures and Acelepryn timing to manage increasing issues caused by climate change.

Find out more tips and tactics for soil pest control on the GreenCast Advisory Blog