Cutting turf growth

There has been a marked increase in interest for growth regulators to restrict turf growth this spring, for a variety of reasons. It can help to cope with a labour crisis and better manage machinery input costs, as well as enhancing turf health and surface quality.

For many turf managers, significant shortages of labour make it more difficult to stay ahead of grass growth, particularly on fairways or semi-rough – or otherwise some turf management priorities have to slip as available staff are committed to keep mowers moving, writes Syngenta Technical Manager, Sean Loakes.

The opportunity for an afternoon cut to clean up greens and maintain speed for evening rounds, for example, is harder to achieve when labour is scarce.

And for others where new equipment is in short supply, keeping an ageing mower fleet working efficiently, by reducing the hours spent cutting, is a huge benefit, along with reduced wear and tear and lower fuel costs.

Many clubs of all types are also investigating robotic mowing on fairways for economies and to reduce labour commitment – where the potential to reduce peak daily grass growth by 30 to 40% with a regular PGR programme could optimise mower performance and turf quality across a wider area.

The question we are most frequently asked, is how often to apply Primo Maxx II, and at what rate?

A huge wealth of science R&D behind Primo Maxx II shows that it works by supressing the turf plants’ gibberellic acid (GA) hormone responsible for growth. Essentially, the more product in the plant, the greater the suppression. Following an application and uptake by the plant, however, the concentration of active ingredient (a.i.) begins to decline and its effects gradually reduce, when the turf starts to regrow more strongly.

The rate at which the a.i. declines can be influenced by a number of factors, often associated around the rate of plant growth and, primarily, temperature – which degrades the product faster at higher levels.

In cool conditions the positive effect lasts longer, so the application interval can be extended; in warmer temperatures the PGR effect will degrade more quickly and so the application interval needs to be closer.

Growing Degree Days (GDD) are a useful tool here to model the speed at which the PGR effect could be reducing, and thereby the speed at which plants will come out of regulation.

However, it’s not an on/off switch, so while GDD is a useful guide to optimum application intervals, plants will come out of regulation gradually, and can be quickly returned back under control with subsequent applications.

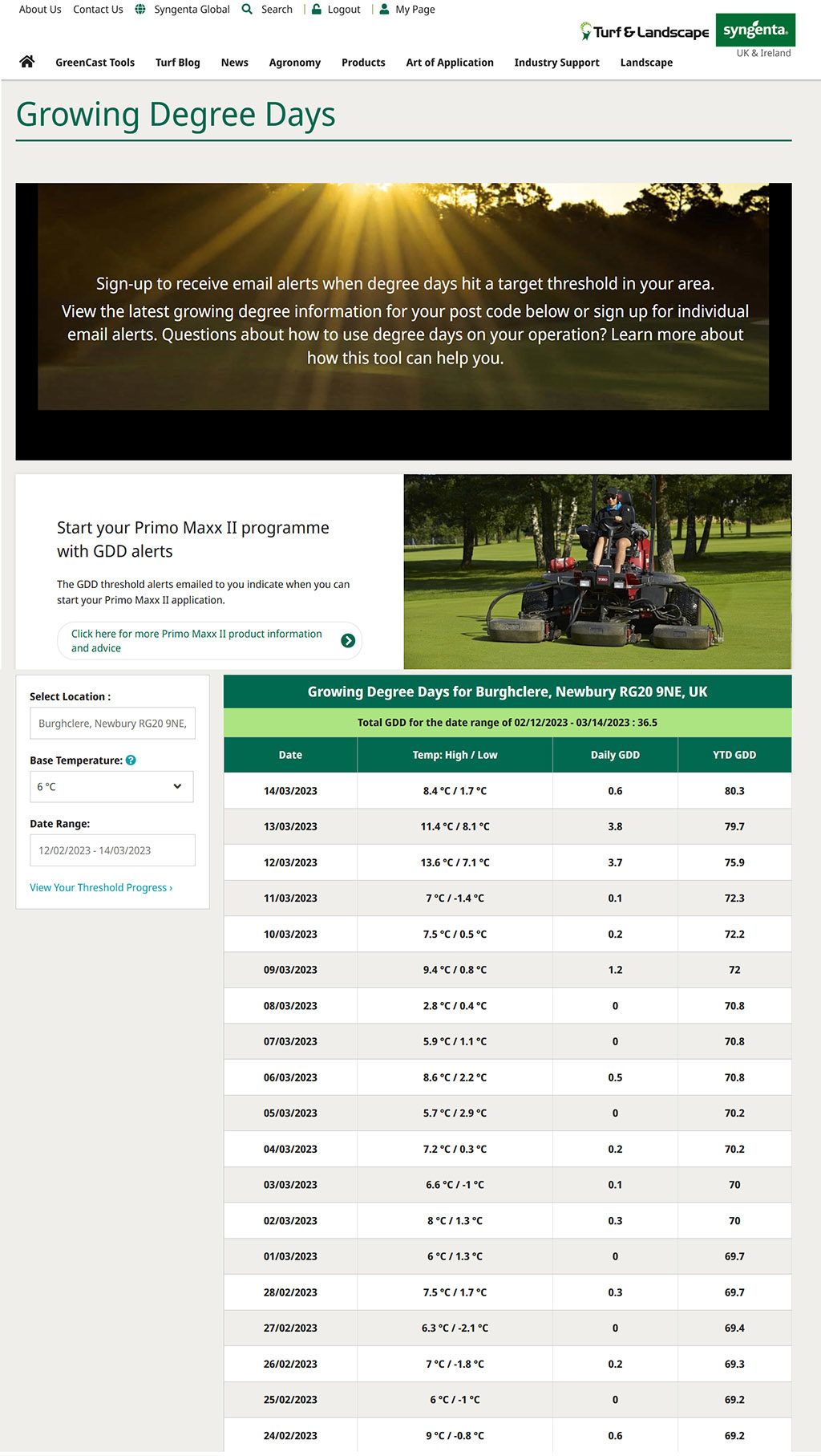

GDD is calculated using data for the maximum recorded temperature, plus the minimum temperature, and then divided by two. Depending on the model used, a base temperature is then subtracted to give a GDD figure for the day. In the UK the base figure is typically 0, 6 or 7⁰C.

That can be calculated manually by recoding the daily max-min temperatures on the course, or from sources of weather records. However, that method takes no account of the daily duration of temperatures suitable for growth, or length of cold nights, for example. It also depends on where any thermometer is situated, or the relative accuracy of data.

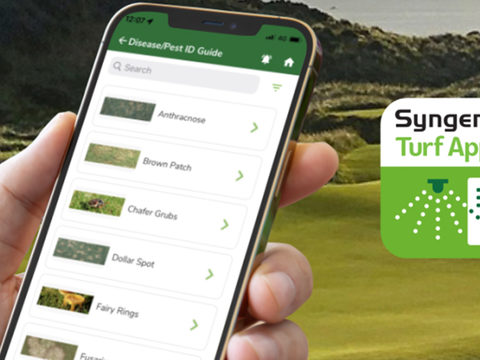

The GDD Calculator - available here - automatically makes the calculation using hourly weather data, which takes account of more of the variables. It gives the option to select a base figure of 0, 6 or 10⁰C.

The results are logged for any selected site, with the opportunity to create different start dates and GDD target figures to fit specific turf management operations. Users can also select a notification of when target GDD figures set to be reached, in time to prepare to take action.

While many turf managers in the UK have historically used a base of 6⁰C, to represent typical timing when grass growth starts, Syngenta analysis has shown that 0⁰C is a more effective base to use, particularly in the early season temperatures in spring, and as conditions start to draw in over the autumn.

One of the world’s greatest exponents of GDD, Dr Bill Kreuser of the University of Nebraska, advocates the use of 0⁰C as the base in his modelling for cool season grasses.

During periods of high growth potential, through late spring and summer, moving to a base figure of 6C could help to smooth out GDD anomalies for a more consistent curve.

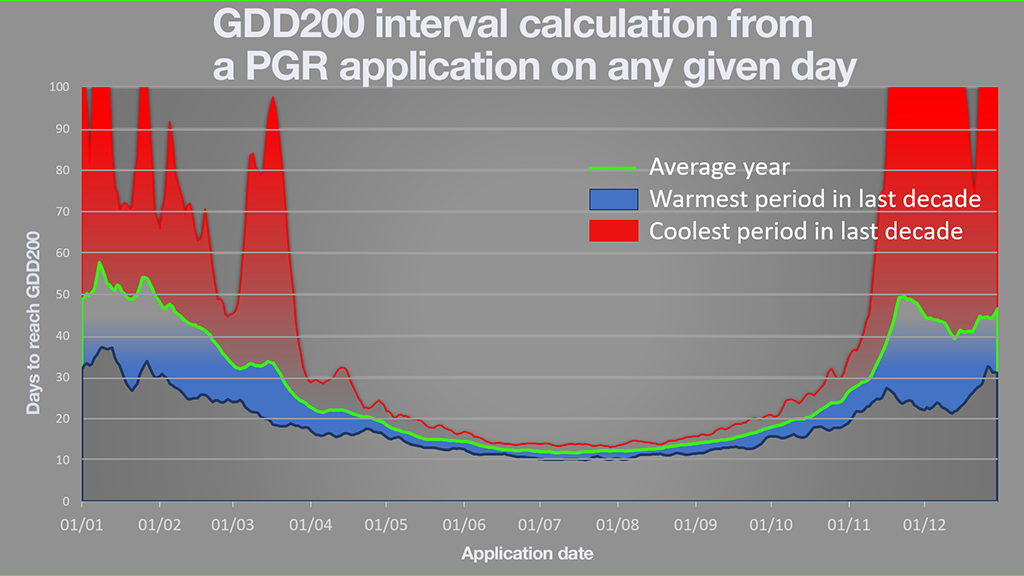

A study of temperatures in the UK (Fig 1.) has shown that through the early spring and at the end of the season in autumn, application intervals at GDD200 could, on average, be over a month apart – shown by the green line. The calculation is using a base of 0 through the year.

From mid-April through to mid-October the application interval would need to be less than 21 days to optimise growth control, which limits turf managers options.

From mid-May to mid-September the GDD200 model demonstrates that 10 to 14-day applications would be necessary to keep turf in regulation.

If the PGR interval were to be extended to 21 days in these conditions, for a label restriction or weather interruptions to application, for example, the turf would rapidly move further out of regulation between treatments and irregular growth patterns occur.

There has been much discussion about a ‘rebound effect’ if PGR effects wear off, but in reality is just turf returning to its unhindered growing state. If there is any difference to an untreated control in trials, it is more likely associated with stronger and healthier plants in plots following the PGR programme, compared to plants that have received no treatment.

While GDD200 has been shown to be a good starting point for most Primo Maxx II programmes, experience will indicate how that might be tweaked to best match any specific site’s growth or individual’s desired levels of growth control.

A high-fertility, parkland setting, for example, may find a GDD180 better suits the level of consistent growth control required, compared to another site where a GDD220 may deliver precisely the level of regulation desired for that course. Adaptations for fairways and greens may also be considered.

Where all other factors affecting growth are unlimiting, such as moisture, nutrition or light, for example, then GDD is an excellent tool to tailor PGR application timing, particularly on the more consistent conditions of greens.

However, if there are other factors that are naturally compromising turf growth, such as drought on unirrigated fairways, it may be judicious to pull back on PGR applications, even when GDD targets are being triggered.

Monitoring grass growth or clipping yields is a good guide as to when to reinitiate treatments, along with the growth potential of turf at any given time.

That is where the experience of the turf manager in understanding and interpreting the data is so important.